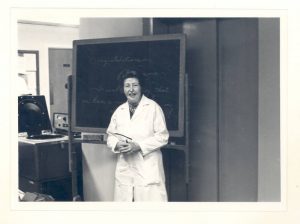

Virginia Minnich (1910-1996) suffered severe, disfiguring burns as a young child but she refused to hide. Instead, she went on to become a noted hematology researcher and the first person without a PhD or MD appointed Professor of Medicine at Washington University at St. Louis (WUSTL).

Virginia Minnich (1910-1996) suffered severe, disfiguring burns as a young child but she refused to hide. Instead, she went on to become a noted hematology researcher and the first person without a PhD or MD appointed Professor of Medicine at Washington University at St. Louis (WUSTL).

Virginia Minnich was born on January 24, 1910 in Zanesville, Ohio and raised on her family's farm along with five siblings. When she was four years old, her dress caught fire on a stove, causing severe burns that, despite dozens of corrective surgeries, left considerable scarring to her face, neck, and upper body. Throughout her life, the scarring led many colleagues to discourage her from jobs requiring much human interaction and give her unsolicited advice on accentuating her “more attractive” features.

She had wanted to become a nurse, but was discouraged from this career path, so she decided to study to become a dietician, receiving a Bachelor of Science in Home Economics from Ohio State University in 1937 and a master's degree in Nutrition from Iowa State College in 1938. She decided that being a nutritionist wasn’t the right career for her after all so, after graduating, she wrote to hematologist Carl Moore, whose lab she had briefly worked in at Ohio State University, asking for a job (assertiveness for the win!).

Moore was in the process of establishing a Hematology department at WUSTL and offered Minnich a technician position. Minnich accepted and helped build the department that would be her home for the remainder of her career (except during her international travels). Minnich quickly established a reputation as an exceptional morphologist, able to extract detailed information and draw conclusions from smears of blood and bone marrow under a microscope. When staining methods or blood tests were sub-par, she would develop her own. She attributes much of her early training to the female chief technician when she arrived at WUSTL, Olga Bierbaum, with whom she became close friends.

Minnich's research encompassed a variety of hematology and nutrition topics. A few highlights:

- From 1949 to 1951 she worked with William Harrington in a landmark study involving self-experimentation – starting with Harrington, the team (including Minnich) injected themselves with blood from patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, leading their own platelet counts to drop and showing that an immune response was leading to platelet destruction.

- In Thailand in 1951, Minnich found an unusually high rate of thalassemias, blood disorders characterized by decreased levels of the oxygen-carrying molecule hemoglobin. Upon further examination, she discovered that this was an undescribed form of thalassemia involving a novel abnormal hemoglobin molecule, hemoglobin E (HbE) (you can learn more about HbE in this companion piece. Her work led to further research into this disease, which is estimated to affect a million people worldwide. HbE is considered to be one of the most common genetic mutations and testing for HbE is now part of routine neonatal screening and genetic counseling.

- In 1965, while in Turkey setting up a hematology laboratory at the University of Ankara, Minnich noticed a form of pica involving clay eating. When she followed up this research upon her return to Washington University, she found a similar clay eating practice in parts of the United States. Pica had been known to be associated with iron deficiency but the cause/effect relationship was unclear; Minnich found that that clay actually made iron deficiency worse by acting as a chelating agent, binding iron in the bloodstream and removing it from the body.

- In 1970, a former colleague, Dan Mohler, referred her to a family with a glutathione synthetase deficiency, leading her to develop and perform biochemical assays to elucidate the glutathione synthesis pathway.

Minnich didn’t keep her talent to herself: she was regarded as an excellent teacher and, in addition to her official teaching responsibilities, she gave informal "night courses" to pathologists, lab technicians, and others. She created a series of audiovisual teaching materials describing the morphology of blood and bone marrow that were published by the American Society of Clinical Pathologists in the early 1980s as a 10-part course in morphologic hematology.

Despite her accomplishments, Minnich, like many female scientists, faced gender discrimination, in particular with regards to her salary. She was interested in going to medical school, but Moore dissuaded her from seeking further education and, consequently, her salary and career advancement were held back compared to men doing similar work. At one point, fed up after a male colleague received a tenure-track position over her, she wrote to the Rockefeller Institute asking for a job, and took the letter to WUSTL leadership as a negotiating chip: acknowledging Minnich’s value, WUSTL offered her a position as research associate professor. She would later (1974) become a full professor of Medicine in 1974 (the first person without a doctorate degree to reach this rank at Washington University). She became professor emeritus in 1978 and retired in 1984. She also worked at Barnes Hospital in St. Louis from 1975 to the mid-1980s as assistant and then associate director of Hematology.

Minnich retired from Washington University in 1984. She died of ovarian and colon cancer April 26, 1996 in Pensacola, Florida. She willed her estate to the Washington University School of Medicine to be used for student scholarships, and Washington University established a visiting professorship in clinical hematology in her name.

This article may look a lot like Minnich’s Wikipedia page – but, don’t worry, I didn’t plagiarize someone’s work – I created Minnich’s article because, despite her amazing life story and accomplishments, she, like countless scores of women in science didn’t have one. Whether it’s creating articles from scratch or expanding and improving existing articles – even simply adding references when you have a few minutes here or there – editing the Wikipedia pages of female scientists is a great way that you, yes YOU, can help increase recognition of the accomplishments of women in STEM and make sure that stories like Minnich’s don’t get forgotten!

Photo Credit: Bernard Becker Medical Library

[sharethis-inline-buttons]